Games for Children and Keith Wilson’s Experiments With Flight

“If it means Icarus to some readers, fine… But my meaning is specific: it is about Black people who could fly.”

— Toni Morrison, in a conversation with The New Republic (1981)

I remember first reading Song of Solomon in an English classroom that smelled faintly of lemon disinfectant, the windows smeared with a thin film that made the view of the parking lot look like a watercolor someone had left to run. We lingered on the final scene, Milkman leaping toward Guitar, “surrendering to the air,” and the teacher asked what flight symbolized in that moment. Flight, of course, is no stranger to Morrison’s mythic family saga. The book’s titular Solomon simply lifts himself into the air and flies to Africa, leaving behind his wife, Ryna, and twenty-one children. The book’s opening scene features the insurance agent Robert Smith announcing his will to “fly from Mercy to the other side of Lake Superior,” jumping from a hospital roof wearing blue silk wings. I said something earnest and tidy about freedom, and she smiled the way teachers do when the real answer was still somewhere else.

Only later did I understand that Morrison perhaps wasn’t offering a metaphor but instead recovering a fact of folk imagination, a story that was once vivid enough to terrify those who tried to ground it. As Morrison writes, there’s a long lineage of African-American folklore centered around flying Africans, folk stories featuring Africans who turned into birds, or of bodies that unstitched themselves from chains and soil and rose as a communal insistence that the world’s limits do not apply to the interior geography of a people. That same insistence—flight as a refusal of imposed category—animates Keith Wilson’s Games for Children.

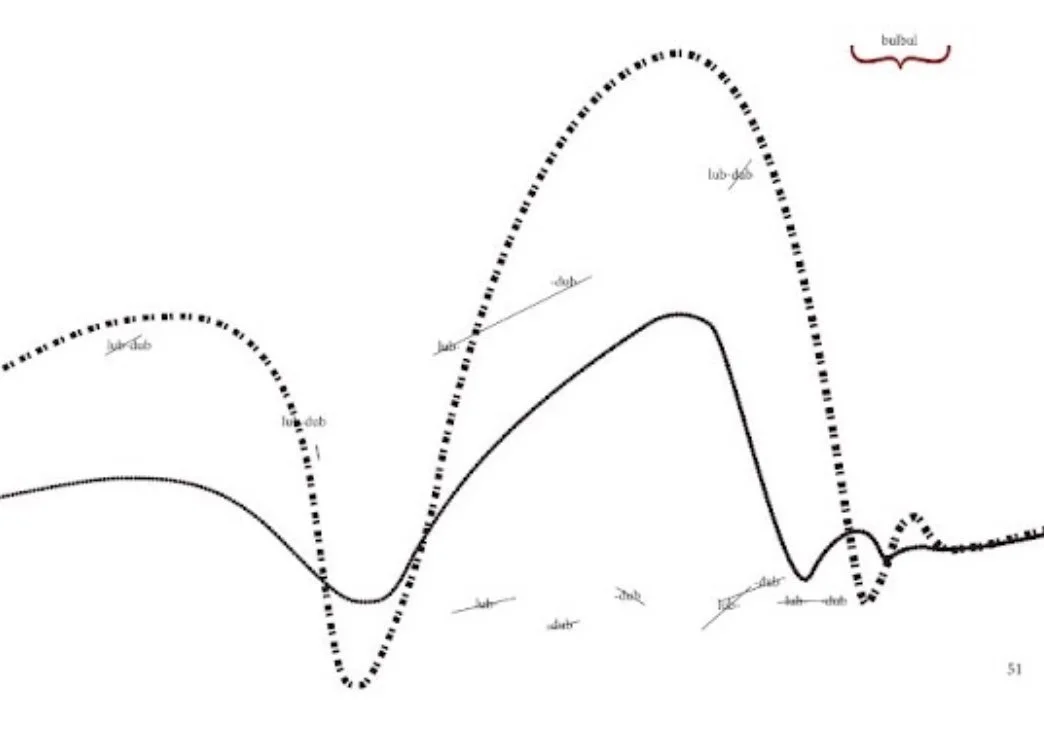

Wilson’s visual poem “Uncanny Pump Fake” epigraphs the same Morrison interview quote, staging her argument in visual terms. The piece is a panoramic compositional field, with two lines running in a cardiogram form across white space, black dashes and dots forming repeated peaks and troughs. Printed along the waveform, dozens of lub-dub labels appear in typographical stuttering; brackets group beats, instructing the reader on sound; tempo marks and short diagonals prick the surface. Then, at a final luminous peak, bracketed and annunciated, a red word appears: bulbul, the name of a songbird most commonly found in Africa. Here, Wilson literalizes Morrison’s myth: the pulse, under duress or under quiet, accrues a capacity for flight.

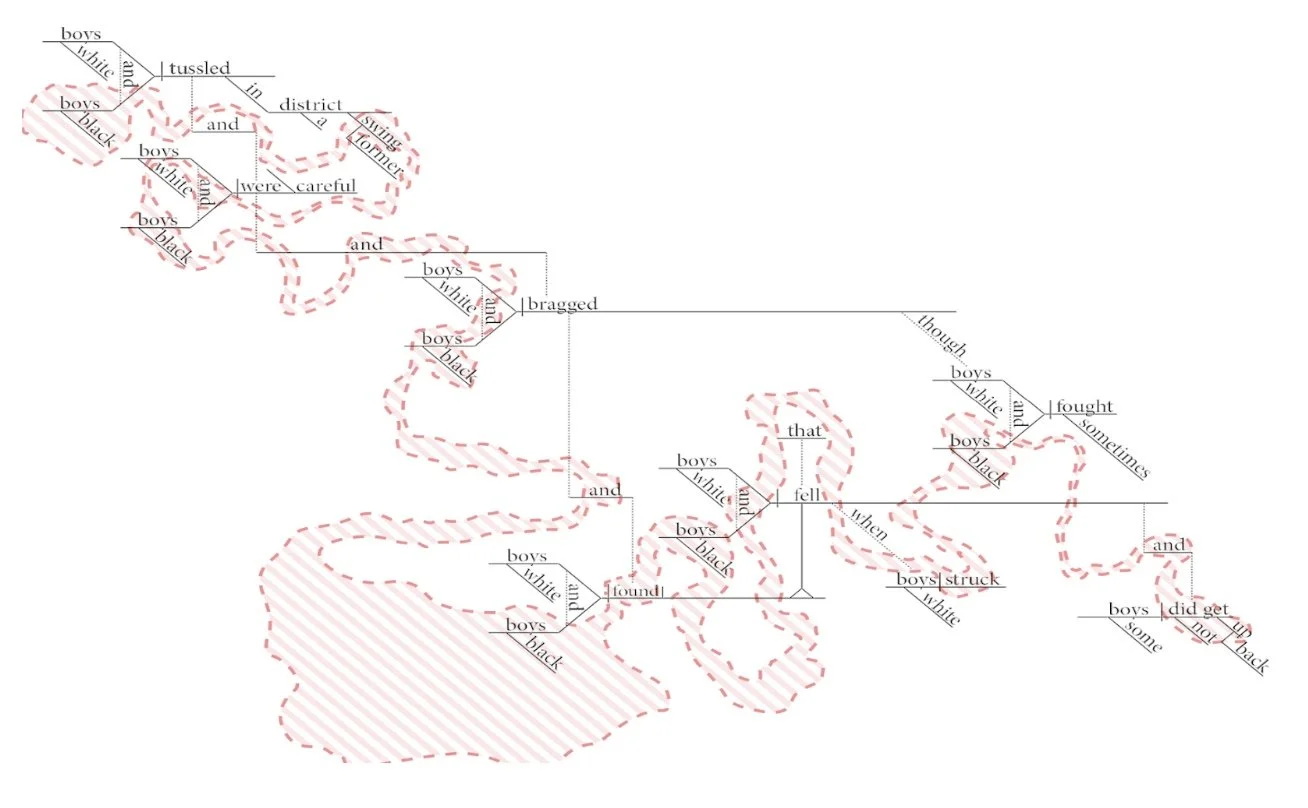

Flight is no stranger to Wilson’s sophomore collection, either. In an interview with the Chicago Review of Books, Wilson explains that in his debut poetry collection, he recalls working through his father’s illness while writing, but in Games for Children, he purposefully tackled American racial history and violence. As he explains, the history of American violence—from slave insurrection to mass incarceration—”is so incomprehensible,” he found that “simple” language often failed to fully capture it. To bridge that gap, he added games, math, and diagrams to his poetry, instead treating language as an object. Wilson describes this object-oriented mode of written art in making his diagrammatic poem “Gerrymander For A Black Sentence,” where his visual intervention superimposes a gerrymandered political map onto a sentence diagram.

In this poem, the familiar geometry of a Reed-Kellogg diagram, all clean angles and grammatical hierarchies, displays the “black sentence”—”white and black boys tussled in a district…”—which is anatomized into its constituent parts. But then the red arrives, a violent, looping outline that snakes around the diagram and coalesces into a single hellfire-hatched lake housing “black boys” at its eastern delta. Its dashed perimeter corrals “black” and “white” into a closed-off curvature and an expansive outgroup of whitespace, visually annotating how our receptiveness to language, like the way in which we are districted, is never truly a race-blind act. There is, Wilson notes, a decisive red line whose ingroup and outgroup represent who gets to occupy what space within meaning, who must be subordinated, who must modify, and who stands as subject.

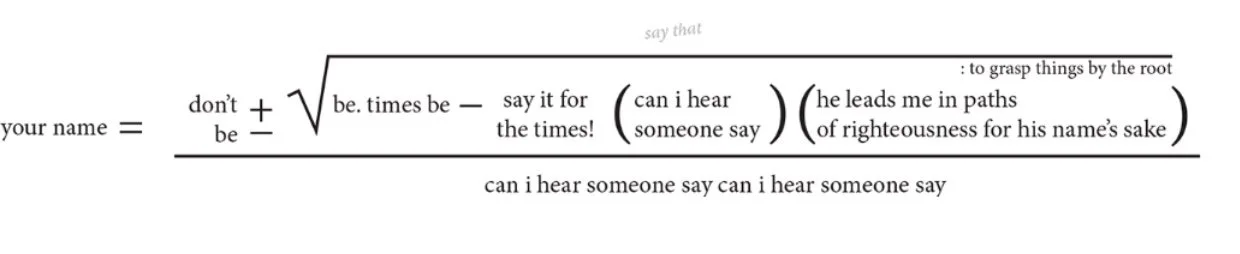

This kind of racial subjectivity, in Games for Children, is rarely not rendered in the visual medium, and Wilson’s transpositions rarely fail to infuse that subjectivity with more meaning. In “spell to trace a rainbow to its apogee,” a poem dedicated to Trayvon Martin, “who dreamed of being a pilot,” Wilson imagines a boy whose dream of flight is transposed into an equation determining the limits of it. In his notation, the formula for solutions to the quadratic ax^2 + bx + c is reimagined with new coefficients:

Let a = “can i hear someone say,” the collective voice that grants or withholds audibility; let b = “be,” the assertion of self; and let c = “he leads me in paths of righteousness for his name’s sake,” the line from Psalm 23:3 that David declares of the Lord. Reading these coefficients together as a trajectory makes the poem’s politics immediate: b is the pilot’s initial thrust (young Trayvon’s desire to become a pilot, the impulse of existing as a subject aiming upward), a the airframe of public insistence, and c the ballast of scripture that orients a path. When these forces exist inside a formula, the image of flight becomes a testable trajectory, and the institutional counterforces that greeted Trayvon—the encounter that ended his flight—turn a potential parabola into a truncated arc. Or, in the poem’s terms, denied him the full horizon he deserved.

The poem constructs the book’s recurring moment in which the child’s dream of lift meets the material fact of atmosphere. In Games for Children, that tension animates Wilson’s treatment of wonder itself, where flight is never an uncomplicated escape and always involves a resisting force. The book’s wonder, then, is always double-edged, in that it gestures upward, toward what Morrison once called the “air,” while keeping its eyes trained on the mechanisms that make air difficult to breathe.

“I’ve always been very interested in wonder,” Wilson says on Games for Children, which is an interest that—thrillingly—coexists with the collection’s political teeth. There’s obvious risk to including both a childlike wonder and a grim political reality in one book of poetry, which Wilson knows and clearly avoids. There’s also risk to the experimental strategy Wilson takes to get these two messages across, and he of course knows them as well. A sentence diagram that’s supposed to resemble a gerrymander can feel at first like a gimmick, and a mirrored stanza can flirt with novelty at the expense of pathos. In Wilson’s best moves, form and feeling expertly coexist. When they fail, the book can become an attractor field for cleverness, but registering that occasional failure also means acknowledging how dangerously difficult his wager is, because to make a new documentational grammar carries the risk of the grammar itself becoming spectacle.

Whether Wilson’s experiments “worked” or not, though, was rarely what preoccupied me when I was reading his collection. I remember going through my day with a line lodged like a pebble in my mouth, and that every time I tried to step back into Wilson’s wonder, I found it shaded by an unease that felt, frankly and increasingly, necessary. The book’s games, then, are not really childish at all but rather expose the quiet logics that organize who gets seen and how. It’s a rare book that rearranges your habits of attention without announcing that it’s doing so, and rarer still to feel that shift as a recognition of what was already there, a sense that the real experiment was taking place long after I’d closed the cover.

Somewhere in that post-read afterglow, I caught myself observing a street sign as if it were a diagram of Wilson’s own making, rife with secrets. I felt ridiculous and also, in a way I can’t quite explain, exactly right.

Rishi Janakiraman is a poet and essayist who writes from Raleigh, NC. He has been recognized by the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, Urban Word, Young Poets Network, Bow Seat, and Best of SNO. A Top 15 Foyle Young Poet of the Year, his work has been published in The New York Times, The Poetry Society, Rust + Moth, and Dishsoap Quarterly, among others. He serves as the Co-Editor-In-Chief of Polyphony Lit and as the NC Youth Poet Laureate.