Amarys Dejai in Conversation with Cuban-Peruvian Poet Sara Daniele Rivera

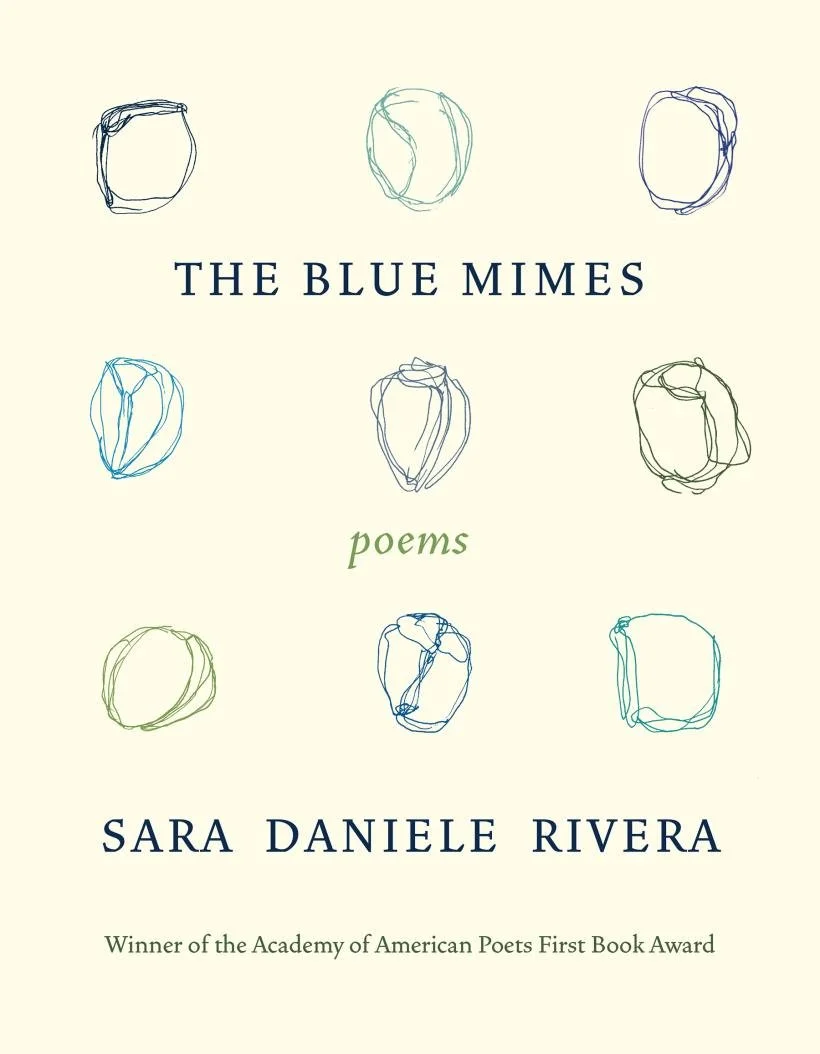

Sara Daniele Rivera is an artist, educator, and author of the poetry collection The Blue Mimes (Graywolf Press, 2024), which explores themes of grief, caretaking, and survival. In this conversation with Sontag Mag Staff Interviewer Amarys Dejai, she discusses inspirations behind her debut collection, simultaneously navigating the “in-between spaces” and “survival,” and the importance of community collaboration.

I'd like to begin by thanking you for speaking with me today. When I was considering interviewees for this issue, I remembered attending the Texas Book Festival last fall here in Austin. You were on a poetry panel with Cindy Juyoung Ok, and I really enjoyed the discussion. So I'm especially grateful for the chance to speak with you now. To start, I’d like to talk about your debut poetry collection, The Blue Mimes, released last year by Graywolf Press. I found the title intriguing—when I think of mimes, I picture street performers using exaggerated gestures. Is that in line with the idea behind your title?

Yes. There’s a poem in the book that is titled “The Blue Mimes," and that is where the entire collection stemmed from. At the beginning of the poem, there's a little scene from a trip I took to Peru in 2014 to visit my family in Lima. This was after my grandfather had died, and we were taking care of my grandmother, who had Alzheimer's. It was a time when there was a lot of grief, and it was my first time back in Peru after many, many years away. So, there was a kind of disjuncture between re-experiencing the city and the country, my being in that city and country again, and the slow pace of being a caretaker. We were driving along la costa verde outside of Lima, and we came to a stop in this taxi. Outside the window, two street performers were doing some sort of miming. They were dressed in iridescent blue, had painted faces, and were doing these slow movements. I saw them for a second, and then we pulled away. I was like, did I hallucinate? Is that a real thing that just happened? But it sort of gave me a language to start writing about what I was experiencing: both the slow experience of that trip and of caretaking, the way dementia affects the pace and movement of the body, and also as a way to talk about grief and how you go through these sort of stilted, mimicking motions of approximating being a person as you're trying to get through something. So I think that's why that stayed in the foreground of the collection, because it continued as these thematic threads.

Thinking back on what I learned about you and your work when I was preparing for our conversation, the word, or maybe the idea, of “survival” has stuck with me. You’ve talked about your grandfather’s dementia, and it brings to my mind words such as “caretaking” and “perseverance." So, I wanted to ask: how does the idea of “survival” play into this book, if at all?

There’s something about the process of writing this book that’s deeply tied to my own survival through some extremely difficult years. My grandfather died, both of my grandmothers passed away during COVID, far away, and much of the book is dedicated to my dad, who died very unexpectedly in 2017. There were so many moments during those years when I didn’t know how to get from one moment to the next, especially after losing my dad.

Writing had already been a part of my life, but during that time, it became essential—something I did just to make it through. I wasn’t thinking in terms of poems or a future book. I was journaling, trying to get something out so I could function. Just putting it down helped me feel a little lighter, a little more able to move through the day. Eventually, going back through those journal entries became the foundation for many of the poems in The Blue Mimes.

While we’re still on the topic of your writing, I saw that you’ve described your work as using both “speculative” and “realistic” lenses. Could you talk a bit more about what that means to you and how those approaches show up in your poetry?

In addition to poetry, I also write speculative fiction, so sci-fi, fantasy, surreal, gothic, and magical stories. But I think of a speculative lens as not tied to genre. It’s about how we tell real stories about our lives when a factual account doesn’t quite capture the truth of an experience. Sometimes you’re trying to write into a fracture, whether it’s a traumatic memory you can’t fully recall or a piece of family history lost to migration or assimilation. There are moments where a literal retelling just doesn’t feel adequate. That’s where speculative techniques come in, not to distort reality, but to get closer to the emotional or spiritual truth of it.

There’s a poem in the book called "Rompecabezas," which centers on two girls who were my grandfather’s older sisters. I didn’t know about them growing up. I knew about his living siblings but only learned a few years ago that he had older twin sisters who died young. No one remembered exactly how. My mom mentioned an earthquake. One may have been hit on the head, the other possibly died at birth. The story was so fragmented that I became obsessed with it. I kept trying to recreate it, to give them a voice, to imagine their lives.

The poem places them in a real scene, invents a version of their life and death, and then gradually unwrites itself, and it falls apart by the end. None of it happened, factually. It’s more like a conjuring of ghosts. But it felt like the only way I could tell that story.

So even when I’m not writing overtly speculative fiction, that lens still shapes my work. I’m recently inspired by authors exploring speculative memoir—writers like Carmen Maria Machado and Jami Nakamura Lin—who are figuring out how memory, imagination, and truth can intersect.

That’s really interesting. Do you find yourself more drawn to one lens over the other—speculative or realistic—or does it depend on what you're trying to communicate in a piece?

It depends on what I’m trying to communicate. I think it goes back to the literal and figurative modes in poetry and language. There are times when you want to be documentary, to capture something as real and direct as possible. But then there are other times—even at the level of language—when a literal image shifts into something metaphorical or symbolic. Sometimes the figurative is what gets closest to the emotional truth. Other times, it’s the plain, straightforward account of what is physically happening that carries the most weight. I’m always interested in how those two modes work together in poetry and how they constantly inform each other.

In reading your work, I’ve noticed you often write about the in-between—whether it’s life and death, presence and absence, or emotional states that feel suspended. In your poem “Sol,” for example, you write, “Some days I’m a pendulum that exists on a planet / that periodically loses gravity.” That image really struck me. This is a broad question, but what draws you to these in-between spaces?

I don’t know if it all stems from this, but at the heart of the book is the experience of being in between, especially as a second-generation child of immigration. You don’t fully belong to one culture or another. You don’t fully belong in one space or another. That can leave you feeling suspended, unsure of how to understand who you are. I’ve always felt a bit in between. I grew up in a bilingual household, constantly moving between languages, which made those boundaries feel porous. And for whatever reason, I was always drawn to speculative fiction and storytelling—stories that live between dreams and reality, and that explore uncertainty or transformation.

I think I’ve moved through a lot of in-between spaces in my life, and over time, I’ve come to see them as rich with tension and possibility. Rather than seeing those states as forms of lack, I try to write toward them, to understand them through the act of writing.

That’s especially true in the poem you mentioned, which is about my dad and the experience of grieving him. Grief can place you in those nebulous states where you're not fully present in your life, but you also can’t fully step away from it. You’re moving through a gray zone of existence. I think many emotional states feel like that, and I’m drawn to writing into those moments.

I see you have done quite a bit of translation, which I really admire as someone who only speaks English. I tried learning Spanish and took four years of classes in high school and college. I was good, but I lost much of it since I didn’t live with anyone who spoke Spanish and couldn’t practice regularly. I’d love to start learning again and become bilingual one day.

All of this makes me further appreciate people who speak multiple languages, especially since I teach ESL students. It’s amazing to watch them acquire a new language.

Maybe I’m thinking too much about this, but I imagine there is a huge responsibility in translating someone else’s words into another language. For me, it feels like an admirable act that is much bigger than myself. How do you approach this responsibility and make sure you stay true to the author’s intent?

That’s really interesting. I first started translating in grad school during my master’s program at Boston University. There was a translation seminar, and at the same time, I took a course in the Latin American Studies Department—taught in Spanish—on contemporary Latin American literature. For that class, I completed a translation project. Before that, I had never done literary translation or translated poetry, and I found it incredibly fun and enjoyable.

I was also new to many of the writers I translated. Until then, I mostly knew the big names you often hear in Latin American literature—Octavio Paz, César Vallejo, Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende. But there are so many other writers I had never been exposed to. I was just beginning to discover them. Many of these poets influenced my book, including Alejandra Pizarnik and Blanca Varela, whose work I have translated.

At the time, I didn’t fully grasp how important and beloved these writers were in their countries, or how often they get erased in the international literary scene. If I had, I might have felt more pressure to capture them perfectly. But instead, I was simply moved by their work. Their poetry was unlike anything I had read before. Their voices opened up new parts of my own voice, especially the Latin American women poets. For me, translating was incredibly exciting. I always aimed to honor what was on the page and to learn as much as I could about the poet to respect their time and context. The book in translation I did was a collaboration with my friend, Lisa Allen Ortiz. Our process was joyful, full of problem-solving.

When I translated the Blanca Varela book, I worked often with my dad, who helped edit the translations. We had a lot of fun with it. Translating living poets is a bit different because you can ask them questions about their intentions and what they want to convey. With poets who have passed away, you can’t ask, so sometimes you have to take a leap of faith and do your best to capture what you see in their work. I believe there is a real responsibility in translation—a responsibility to be a conduit for words that are not yours and to honor the original poem as much as possible. Sometimes that means capturing the meaning, other times the music, the tone, or the emotion. Different poems require different things. I approach translation with a great deal of respect, but it still feels more joyful and playful than heavy to me.

I also noticed that you’re an artist as well, and much of your work takes the form of public installations and community-based projects. A lot of it invites people to be part of the process, as art often does. I’m curious: How does it feel to have your community, or even complete strangers, involved in these art projects? What is that experience like for you?

It’s incredible, and it’s really what I came to want from making art. I earned one of my undergrad degrees in studio art, focusing on sculpture. When I was in art school, the experience was very gallery-based. At the time, I didn’t know much about the art world beyond what I learned in art history classes. I had this idea that being an artist meant working in a gallery, creating a product to be displayed, sold, or consumed. I worked in that world for a while but eventually became uninterested in it.

One of my first jobs after grad school was with the Urbano Project in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts. We created collaborative art with youth, working around social justice themes that affected their neighborhood. I facilitated their involvement in making installations or other artworks. That process was activating and illuminating for me. I also did a lot of theater in undergrad, especially devised, collaborative, experimental theater. I loved that kind of theater because you didn’t know what the final product would be. Instead, you explored and created the story together. When I applied that collaborative approach to installation art, sculpture, and public poetry projects, it brought that energy back.

I get to provide my tools as an artist, whether those are materials or educational exercises, and work with the community to discover the stories they want to tell and the art they want in public spaces. For example, in my last installation, I taught a group of young people to cast gypsum, and together we created a sculpture prototype. This way, I create art not for a gallery wall or consumption, but for the city and community—art that belongs in the public spaces where people live and gather.

I was looking at the various art projects you have done within classrooms, like having students create letters or use texts from interviews to build larger works. For example, the “Friends of the Orphan Signs” and the “Pudding Rock Banner,” among others. As I thought about these projects and installations, it occurred to me that they seem to push back against disappearance. They bring attention to different cultures and make these presences known. Maybe I’m off, but would you say that this is part of your purpose or motivation for these art projects?

That’s beautiful, and it really connects with something I’ve been thinking about. Many of my recent projects involve sculpted texts displayed in public spaces. For example, during my time as a Story Maps Fellow at the Santa Fe Art Institute, I worked on the Youth Work Pathways Project. I collaborated with teens who had fallen out of the school system, been previously incarcerated, or were unhoused. The organization supporting them did incredible work providing wraparound services.

I spent a lot of time with these young people, writing poems with them and hearing their stories. Together, we created installations, like a clay pathway poem in a classroom and adobe letter sculptures at the Art Institute. There was something deeply therapeutic about shaping these materials and giving physical form, weight, and presence to their stories and words—stories that can easily be erased, ignored, or forgotten. Talking with these teens, many of whom face incredible challenges like strict parole requirements, taught me a lot. They are trying to reintegrate and build lives, but the systems meant to help them often end up holding them back. For those without this experience, it’s easy to blame the individuals rather than the failing institutions. That makes it all the more important to give these stories a platform.

The creativity, emotion, and brilliance of these young people are remarkable. Creating art that occupies real space sends a message: We are here, our experiences matter, and we are part of this city. Being part of that process feels meaningful. I also feel like I’m always learning from my students. Teaching has been a cornerstone of my career, and I love the relationships it creates. Whether coaching tennis or teaching in classrooms, I strive to avoid hierarchies. I want my students to be collaborators, co-artists, and co-creators rather than just recipients of knowledge.

Every group of students brings its own knowledge and creative processes, and I’m constantly learning how to be a better educator from them. In the arts, I see my role as a cultivator of community and collaboration, a conduit for shared knowledge rather than its sole source. That is something I continue to learn from my students every day.

To wrap up, I have one last question for you. Across all your work—your sculptures, art, poetry, and writing—is there one guiding idea, moment, memory, or phrase that you keep coming back to? Something that consistently influences or inspires you?

That’s a big question, and I’ll answer it in a roundabout way. My book features line drawings—some I made and some by my dad. I’ve often been asked why they’re there, and only recently have I been able to explain it clearly.

In high school, I loved drawing photorealistic portraits of family members and places I wanted to see. I was obsessed with capturing fine detail. My dad, however, drew in a very different way—gestural and abstract. He encouraged me to move beyond photorealism and focus instead on what a drawing could do that a photograph couldn’t. He taught me about the kinetic energy in a line—the way lines can trail off or remain unresolved, searching for their true form.

That searching quality is at the heart of my book. As I wrote, I realized the collection was really about the search for meaning—searching for connection in grief, for understanding of identity, for those in-between liminal spaces. It’s like the collaborative creative process itself: stepping into a vulnerable, energetic place where the final product is unknown, but discovery happens through the act of searching together.

In art school, I heard the gestural line described as a “searching line,” and I keep returning to that idea, whether in text or image. The act of searching has become a guiding practice for me.

Sara Daniele Rivera is a Cuban/Peruvian artist, writer, translator, and educator from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her writing has appeared in The BreakBeat Poets Vol. 4: LatiNext, Solstice, Waxwing, Speculative Fiction for Dreamers: A Latinx Anthology, and elsewhere. She was the recipient of a 2017 St. Botolph Club Emerging Artist Award, the winner of the 2018 Stephen Dunn Prize in Poetry, and a 2022 Tin House resident. She is a co-translator of The Blinding Star: Selected Poems by Blanca Varela (Tolsun Books, 2021) and co-editor of Not Your Papi’s Utopia: Latinx Visions of Radical Hope (Mouthfeel Press, 2025). Her debut book of poetry, The Blue Mimes (Graywolf Press, 2024), won the 2023 Academy of American Poets First Book Award.

Sara's poetry and fiction use both speculative and realist lenses to explore themes of grief, migration, memory, and the liminal spaces between language and silence. Her drawings, sculptures, and installations focus on text-in-space as social intervention and draw on practices of communal storytelling to bring moments of curiosity and tenderness to public art. She often develops projects through community-based collaborations. She translates between Spanish and English, focusing primarily on Peruvian poetry. She lives in Albuquerque with her son, husband, cats, and turtles.

Amarys Dejai is a multifaceted writer from Austin, Texas. Her poetry and prose have been published by Local Wolves, Foglifter, and others. In addition to working with Sontag, she is the Director of Writing for the Austin-based art and creative magazine Glaze, a music journalist for the press outlet Punkaganda, and a staff writer for Hayat Life Magazine. Alongside being a writer, she is a photographer, artist, and educator.